The past year has witnessed a landslide of global participation in Massive Open Online Courses. These classes are commonly referred to as MOOCs and have attracted a diverse range of students from across the globe. In addition to massive enrollment figures (spilling over 100,000 in some cases), these courses are unique in that they are offered by some of the top universities in the United States and the world– for free.

Last month one million users registered with Coursera, making it the most popular MOOC site on the web. The site was founded only a few months ago, in April of 2012, by computer science professors Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller from Stanford University. A competing MOOC site, Udacity, was also launched by a former Stanford professor, Sebastian Thrun.

It would be remiss not to mention Sebastian Thrun and his role in the MOOC revolution. It was his Fall 2011 Artificial Intelligence class that ignited the spark of MOOC fever that swept the U.S. after enrollment numbers climbed to 137,000. Though only 23,000 completed the course – Thrun said he was hooked on the thrill of teaching massive classes, describing a particular fascination with the peer-based teaching that flourished among the course community.

The trend of MOOCs is spreading not only in the U.S., but to other countries as well. Today, Coursera has a participating university in Canada, India, Scotland and Switzerland. International support for these classes is most evidenced in the international student participation rates. In Thrun’s original AI class, only 25% of the enrolling student body was located within the United States. Independent classes are cropping up across the world in Internet labs and open universities, providing education to those who may not have had access to such information otherwise.

Information is exactly what students of MOOCs are receiving. The classes do not offer degrees or course credits to students who are not enrolled in a parent university, which makes the very purpose of MOOCs different from a traditional institution of higher education. Currently, the most popular courses are in business and technology, suggesting that professors are seeking to answer a need for information within the professional field, making MOOCs relevant and impactful for members of the workforce rather than a student body. There are certificates of completion available for some classes, but the certificates do not carry the title of any university.

Currently, Coursera offers the widest selection of classes of the MOOC sites and has branched out of the STEM box (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics) with humanities courses such as poetry and mythology. Other sites such as edX seemed to be bound to the STEM courses for the simple reason that coursework can be assessed and graded by calculations – in other words, by a computer. Other sites are embracing the concept of a peer-educated community by requiring peers to review original work that cannot be graded by a computer. The quality of such peer-based education has yet to be determined.

Another unknown factor of the MOOC era is how these sites will develop sustainable business models. While the motives behind these startups have been primarily utopian – to make higher education globally accessible – the millions of dollars invested in these new companies demand a for-profit model.

The business model that Thrun has suggested would possibly transform MOOCs into a type of trade school in which qualifying students would agree to have their scores and information sold to recruiting companies. This relationship would support a definition of open courseware that provides education despite barriers of finance or distance; but it could also work to limit courses to relevant industry-related topics.

Katheryn Rivas is a prolific freelance writer and professional blogger who frequently contributes to www.onlineuniversities.com as well as other education and technology sites. If you have any comments or questions, drop Katheryn a line at katherynrivas87@gmail.com.

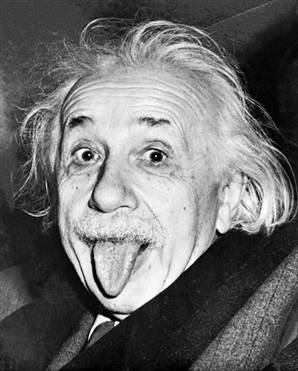

The story goes that a reporter asked Albert Einstein for his phone number (no, this didn’t take place in a bar), and Einstein had to look it up in a phone directory. When the reporter expressed surprise that the twentieth-century’s greatest physicist didn’t know his own phone number, Einstein replied, “Never memorize what you can look up in a book.”

The story goes that a reporter asked Albert Einstein for his phone number (no, this didn’t take place in a bar), and Einstein had to look it up in a phone directory. When the reporter expressed surprise that the twentieth-century’s greatest physicist didn’t know his own phone number, Einstein replied, “Never memorize what you can look up in a book.”