I love being in the classroom, whether it’s large or small, whether I’m officially the teacher or the learner. But I also love getting out of the classroom. Some of the most powerful experiences in my own learning and my own teaching have been observing, interacting, and reflecting in spaces other than lecture halls and seminar rooms. Some time ago, I wrote about place-based pedagogy (with some suggested reading) and gave the example of a workshop for the Educational Developers Caucus (EDC) conference at Thompson Rivers University. Since then, I have continued to use what previously I hadn’t a name for in my own cultural studies course — the field observations and intellectual response papers, the spontaneous “field trips” out into parts of campus to apply concepts, the incorporation of people’s experiences into the framework of the course.

Today’s post is about a small piece of the place-based learning experience I had at the EDC conference, a piece that I’m considering using with my own learners when they do their field observations. To date, I’ve supplied them with reflection questions and notetaking guides for the site visits. I’ve used the online quiz tool in the learning management system to ask “prime the pump” journal questions. But I’ve never yet tried the “transit question” approach. Transit questions were thought-triggering questions handed out just before traveling to the field sites in Kamloops. There were, to my recollection, four different cue cards and each pair of people received one or two cue cards. The idea was that the question on the front (and maybe there was one on the back) would ready us for what we were about to see by asking us about related prior experience with X, or what we expect to find when we get to X, or how is X usually structured. The idea was to talk to our partners about the questions and answer them informally as we made our way to the sites (which took 10-20 minutes to get to).

I can imagine transit questions for pairs that would be suitable for my course too. However, we don’t always have pairs (sometimes small groups, sometimes solitary learners going to a space in their hometown, and so on). I can easily adapt the idea for solo use, though clearly I wouldn’t want someone to be taking notes in response to the prompt while, say, driving!

If we do the field trip to Laurel Creek Conservation area again to test ideas found in Jody Baker’s article about Algonquin Park and the Canadian imaginary, I’ll be using transit questions for the bus ride for sure. With other observations I will have to think about how to adapt the idea. Choosing the right question or questions seems to be important, and offering space to jot notes for those who don’t want to start talking immediately. I’d strongly encourage this approach when you know people will be traveling somewhere for the course by bus, or by foot/assistive device. I can imagine that there are lots of opportunities to do this (and it’s likely already done) in disciplines as varied as geography, planning, fine art, architecture, biology, geosciences, accounting, anthropology, and many others. I’m thinking it would be great if they could pull questions from a question bank to their phones or other devices en route as well… the possibilities!

Transit questions on the way to field sites helped to ready me and my partner for what we’d be looking at, to reflect on the implications of our mini-field trip, and to connect our histories to the present task. I recommend them wholeheartedly.

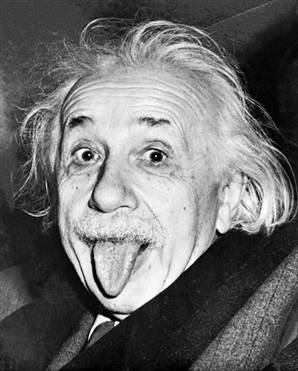

The story goes that a reporter asked Albert Einstein for his phone number (no, this didn’t take place in a bar), and Einstein had to look it up in a phone directory. When the reporter expressed surprise that the twentieth-century’s greatest physicist didn’t know his own phone number, Einstein replied, “Never memorize what you can look up in a book.”

The story goes that a reporter asked Albert Einstein for his phone number (no, this didn’t take place in a bar), and Einstein had to look it up in a phone directory. When the reporter expressed surprise that the twentieth-century’s greatest physicist didn’t know his own phone number, Einstein replied, “Never memorize what you can look up in a book.”