I recently listened to a segment on the Current on CBC, about academic integrity and the effect of technology on cheating. The main guest was Dr Julia Christensen Hughes, Dean of the College of Management and Economics at the University of Guelph, who talked about the findings of some of the research that she has conducted on Canadian university students. A whopping 80% of Canadian university students admit to having cheated. They admit to at least one of over 30 behaviours that are considered cheating at university ranging from outright cheating on exams, to plagiarism, to working in groups when specifically asked to work individually on an assignment. Interestingly this isn’t a new problem. American studies in the ‘60s found that 75% of students admitted to cheating in college. And it’s not a new behavior for students when they get to the post-secondary environment. In one recent Canadian study 60% of high school students admitted to cheating on tests, and 75% to cheating on written work that is handed in. Although technology provides more ways for students to cheat (buying “internet” papers, using online paper mills and just good old cut and paste from internet sites) it hasn’t impacted the overall rate of cheating. Technology has however increased instructors’ ability to detect plagiarism thanks to online services such as Turnitin that use huge data bases of accumulated student work, web pages and online journals to compare submitted work to common sources.

I recently listened to a segment on the Current on CBC, about academic integrity and the effect of technology on cheating. The main guest was Dr Julia Christensen Hughes, Dean of the College of Management and Economics at the University of Guelph, who talked about the findings of some of the research that she has conducted on Canadian university students. A whopping 80% of Canadian university students admit to having cheated. They admit to at least one of over 30 behaviours that are considered cheating at university ranging from outright cheating on exams, to plagiarism, to working in groups when specifically asked to work individually on an assignment. Interestingly this isn’t a new problem. American studies in the ‘60s found that 75% of students admitted to cheating in college. And it’s not a new behavior for students when they get to the post-secondary environment. In one recent Canadian study 60% of high school students admitted to cheating on tests, and 75% to cheating on written work that is handed in. Although technology provides more ways for students to cheat (buying “internet” papers, using online paper mills and just good old cut and paste from internet sites) it hasn’t impacted the overall rate of cheating. Technology has however increased instructors’ ability to detect plagiarism thanks to online services such as Turnitin that use huge data bases of accumulated student work, web pages and online journals to compare submitted work to common sources.

What interested me most from the conversation with Dr Christensen Hughes was her finding that students were less likely to cheat if they respected the instructor, if they felt that the quality of the education that they were receiving was high and if the instructor was using assessments that were truly assessing the skills and knowledge that students were learning in the course. This last point dovetails nicely with a book that I have just been reading, “Cheating Lessons – Learning from Academic Dishonesty” by James M. Lang. Lang discusses how the ways that we teach and assess can impact student’s academic integrity and how instructors can design assessments that reduce academic dishonesty and also create better learning.

Lang proposes that students are more likely to cheat if:

- there is low intrinsic motivation to actually learn what they are being assessed on;

- there is an emphasis on one-time performance rather than continuous improvement towards mastery;

- the stakes are high on a single assessment;

- they have a low expectation of success.

So what can an instructor do to decrease cheating and increase learning?

When students are intrinsically motivated, find the subject matter meaningful and can connect it to their own lives, they will learn more and retain their learning. Students driven by extrinsic rewards, such as grades, use strategic or shallow approaches to learning and will have more motivation to cheat. Posing authentic, open-ended questions to students or challenging them with problems or areas of investigation of their own choice can give students the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge and reflect on what they have learned. Learning portfolios that include journal entries, short essays, and reflections can assess the student learning experience and understanding of concepts (and are darn hard to cheat on).

Learning for mastery (a deep approach to learning) rather than one time performance can be encouraged and assessed. Giving students multiple attempts on assessments or offering students choices on how they will be assessed can promote a mastery approach. These tests can also provide students with feedback so that they can learn from the assessment and then apply their learning again to show mastery. Scaffolded assignments or essays, where drafts and reworked versions are submitted for feedback, can provide evidence of learning and are not likely to be purchased in the internet.

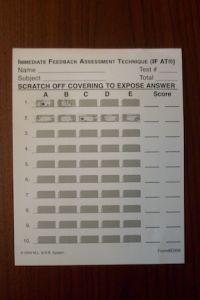

There is evidence that repeated low stakes assessments have the largest impact on learning and retention of learning, particularly if the testing is in the format of short answer questions. Known as the “testing effect” it can be achieved through the use of short online quizzes or one-minute papers. Creating opportunities for students to retrieve knowledge and rehearse answering questions not only measures learning, but also produces learning (Miller, 2011). Lang discusses how taking the emphasis off a one big, high stakes assessment and introducing multiple low stakes assessments helps students rehearse for more substantial assessments and actually reduces cheating.

When students feel that they have no chance of success they are more likely to give up rather than attempting to master concepts, and they may look for alternative, dishonest ways to pass tests. Lang argues that helping students be aware of their level of understanding throughout a course will help them gauge how much work they need to do to be successful on major assessments. Activities like think-pair-share, clicker questions and other in-class activities or formative assessments help instil self-efficacy, and help students identify what they need to do to become capable rather than relying on cheating.

All sounds like more work for the instructor, yes, but with two great results – better learning and less cheating and presumably less time spent following up on academic integrity cases as well.

Lang, J.M. 2013. Cheating Lessons: Learning from Academic Dishonesty. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass, USA.

Miller, M. 2011. What College Teachers Should Know About Memory: A Perspective from Cognitive Psychology. College Teaching, 59:117-122.