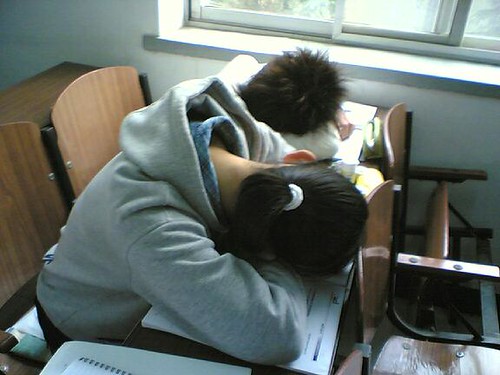

A couple of years ago, I asked someone who kept falling asleep or listening to his iPod during my lectures (even though I break things up with “activities” every 20 minutes or so) why he didn’t just stay in his residence room. He said he always went to lectures in case he might pick up something by osmosis. I’m not blaming the student here — just reminding myself that not every second of my craft needs to be gripping to every single student! The increasing use of laptops in class (especially for MSN, Facebook, YouTube, and other non-course-related stuff) is, however, a very public display of what some would call incivility, or inappropriate behaviour amongst lecture attendees.

A couple of years ago, I asked someone who kept falling asleep or listening to his iPod during my lectures (even though I break things up with “activities” every 20 minutes or so) why he didn’t just stay in his residence room. He said he always went to lectures in case he might pick up something by osmosis. I’m not blaming the student here — just reminding myself that not every second of my craft needs to be gripping to every single student! The increasing use of laptops in class (especially for MSN, Facebook, YouTube, and other non-course-related stuff) is, however, a very public display of what some would call incivility, or inappropriate behaviour amongst lecture attendees.

For the past two days (predictably — it’s the end of term and who doesn’t need a break from grading?) the main discussion list for the Society for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education has been awash in opinions about boring professors and unengaged students. The topic began as a question about banning laptops. Of course banning laptops sounds good to those of us who teach or have observed large first year courses. Until you remember the doodles we did, notes we passed, and other things we did during certain lectures in our own freshman years. Until you remember that some students require laptops to help accommodate disabilities, and banning everyone else’s laptops would “out” them to their classmates. Some good advice came in the form of “use the laptops that show up in class” — which is what I try to do, especially given the possibilities of Web 2.0 tools — and we did get a great reference to an issue of New Directions for Teaching and Learning about this very topic in different disciplines. A quick search of the blogosphere revealed a Chronicle of Higher Education article about this topic too.

This is about more than laptops though.

What concerns me most about the discussion, I think, is that what started as a “blame the lazy millennials” for their lack of civility became a “blame the unprofessional professors” for their inability to keep people awake with entertaining cartwheels (I think I’ll try cartwheels this Winter in my class of 160 students). Blame the students or blame the professors. Pick your side.

I’m simplifying things, but only a little. At least two posters so far have placed the blame for disengaged students squarely on the shoulders of the professors. Ironically, this happens the same day that we find out the data on why students are at university in Ontario and at Waterloo in particular. Sure, 42% really want to be here in an engaged way. Fewer than half. Just over a fifth come because they think they have to, and another fifth have no idea why they bothered. Luckily, a fifth still want to change the world.

http://www.bulletin.uwaterloo.ca/2008/dec/12fr.html

The same holds true of informal polls in a couple of first year courses my spouse and I have taught at another university — fully half the students each year claim not really to want to be at university at all, and cite peer pressure, parental pressure, or just aimlessness as their only reasons to bother going for a degree.

And yet it’s up to us to engage every one of them? Surely, surely it’s a shared responsibility! As a student in the 1980s, when I faced a so-called “boring” lecturer, I saw it as my job to FIND something interesting in the lecture. I was free to leave if I couldn’t. And I knew (as a Trent student) that we’d have a lively tutorial after even the most mind-numbing lecture (there really weren’t many of these; virtually all my lectures in first year were top-notch, and they were delivered by tenured professors, who also ran the tutorial discussions).

This leads me to reflect on the data-driven findings of the Physics Education Research Group at the University of Washington, three members of which visited UW last Friday for the annual Physics Teaching Day, organised by Rohan Jayasundera. They have found time and time again that students CAN in fact improve markedly on basic understandings of fundamental physics concepts through guided inquiry and guided tutorials. This seems to square with the Harvard research on “interactive engagement” techniques (now with clickers) in large lectures. More on next term…